Verb in German. Verbs in German Conjugation of the verb stehen

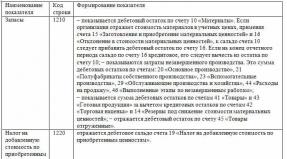

There are two types: strong and weak. Those who have not studied German will find the system of distinguishing them difficult. But this is only at first glance.

The strong differ from the weak in how they behave when conjugated in the singular present tense (Präsens), in the past tense (Präteritum) and in the form (Partizip II)

Partizip II is a verb form that in Russian corresponds to a participle. Mainly used to form the past tense perfect.. Strong verbs, or irregular ones, show significant root changes in all three cases, so the way they are formed must be remembered.

However, here you can notice a certain pattern, which consists in the fact that certain roots from the following turn into such in the present tense form:

1. a - ä fallen - fall

2. au - äu laufen - läuft

3. e - i, ie, ieh, a flechten - fliecht

Some of the strong verbs do not have a personal ending in the first and third person present tense:

ich/er lief

The Präteritum of strong verbs is formed by changing the root vowel, for example:

backen-buk

There is an internal system for distributing verbs according to changes in the root vowel. This makes it easier to memorize special forms.

Partizip II as another distinctive feature of a strong verb

A distinctive feature of strong verbs is also the formation of Partizip II, because in this case, the prefix ge- and the ending -en are added to the main form of the verb, while in weak ones the prefix ge- and the ending -t. Compare:

bergen - barg - geborgen

machen - machte - gemacht

By these signs you can understand whether a verb is strong or weak. If you are careful, everything is simple and clear. Without knowing the basic rules, many are lost, not knowing what the initial form of the verb is, so they go through the wrong options. To make it easier to memorize the formation of Präsens, Präteritum and Partizip II strong verbs, there is a special table that indicates the changes of verbs. German-Russian dictionaries usually include this table, which significantly reduces the time it takes to search for a particular word.

Video on the topic

Tip 2: Declension of German verbs: rules and practice

The system of verbs in German is somewhat more complicated than in English, since in German there is a separate form of the verb for each person, but for a Russian person this is not at all surprising. In addition, the German language has a rather complex tense system; you will find more detailed information about this in the grammar section

Rules for conjugating verbs in German

Verb conjugation in the present tense (Prasens)

To indicate an action in the present or future tense, the tense form Prasens is used. When changing a verb by persons, personal endings are added to the stem of the verb. A number of verbs exhibit some peculiarities when conjugated in the present.

Weak verbs

Most verbs in German are weak. When they are conjugated in the present tense, personal endings are added to the stem of the verb (see fragen - ask).

- If the stem of a verb (weak or strong, not changing the root vowel) ends in d, t or a combination of consonants chn, ffn, dm, gn, tm (e.g. antworten, bilden, zeichnen), then a vowel is inserted between the stem of the verb and the personal ending e.

- If the stem of a verb (weak or strong) ends in s, ss, ?, z, tz (e.g. gru?en, hei?en, lesen, sitzen), then in the 2nd person singular the s at the end is dropped, and the verbs receive ending -t.

Strong verbs

Strong verbs in the 2nd and 3rd person singular modify the root vowel:

- a, au, o receive an umlaut (e.g. fahren, laufen, halten),

- the vowel e becomes i or ie (geben, lesen).

For strong verbs with an inflected root vowel, the stem of which ends in -t, in the 2nd and 3rd person singular the connecting vowel e is not added, and in the 3rd person the ending is also not added (for example, halten - du haltst, er halt), and in the second person plural (where the root vowel does not change) they, like weak verbs, receive a connecting e (ihr haltet.)

Irregular verbs

The auxiliary verbs sein (to be), haben (to have), werden (to become), by their morphological features, belong to irregular verbs that, when conjugated in the present, exhibit a deviation from the general rule.

Modal verbs and the verb "wissen"

Modal verbs and the verb "wissen" are part of the group of so-called Praterito-Prasentia verbs. The historical development of these verbs has led to the fact that their conjugation in the present tense (Prasens) coincides with the conjugation of strong verbs in the past tense Prateritum: modal verbs modify the root vowel in the singular (except sollen), and in the 1st and 3rd person singular numbers have no endings.

Conjugation of the verb stehen

The conjugation of the verb stehen is incorrect. Forms of the verb steht, stand, hat gestanden. Alternating vowels e - a - a in the root: "haben" is used as an auxiliary verb for stehen. However, there are tense forms with the auxiliary verb sein. The verb stehen can be used in a reflexive form.

Conjugation of the verb machen

The conjugation of the verb machen is incorrect.. Forms of the verb macht, machte, hat gemacht. "haben" is used as an auxiliary verb for machen. However, there are tense forms with the auxiliary verb sein. The verb machen can be used in a reflexive form.

Verb sein

In German, the verb (vb) sein can be called the main verb. With its help, tenses and other language structures, as well as idioms, are constructed. German verb. sein in its functionality is an analogue of the English verb. to be. It has the same meaning and also changes its form when conjugated.

German verb. sein as an independent verb. in its full lexical meaning it is translated as “to be.” In the present tense (Präsens) it is conjugated like this:

- Singular (singular)

- Ic h (I) – bin (there is)

- Du (you) – bist (there is)

- Er/sie/es (he/she/it) - ist (is)

- Plural (plural)

- Wir (we) - sind (there is)

- Ihr (you) - seid (is)

- Sie/sie (You/they) - sind (there is)

In the past incomplete tense (Präteritum) it is conjugated as follows:

- Singular (singular)

- Ich (I) – war (was/was)

- Du (you) – warst (was/was)

- Er/sie/es (he/she/it) - war (was/was/was)

- Plural (plural)

- Wir (we) - waren (were)

- Ihr (you) - wart (were)

- Sie/sie (You/they) - waren (were)

The third form of the verb sein – gewesen is not conjugated.

Declension of German verbs

The main (large) table does not contain the first and second person singular forms. This is done in order to make it easier to memorize verbs, and also because these forms are subject to certain rules that are valid for both regular (weak) and irregular (strong) verbs.

The first person singular form differs from the infinitive only in the absence of the final letter -n. The second person singular is most often formed by adding the suffix -s- before the final letter -t to the third person singular form.

Illustrative examples of conjugating verbs of the 1st, 2nd and 3rd person in the present tense are given in the small table at the bottom of the page.

The plural in all persons (except one) coincides with the infinitive: essen - wir/sie essen. This also applies to the respectful address to you in the singular or plural: Sie essen.

There are some exceptions here. If we address several well-known people (friends, colleagues, children, etc.) in German as you, we use the pronoun ihr and add the suffix -t to the root of the verb. Very often (but not always) this form coincides with the third person singular: Ihr bergt ein Geheimnis. - You are hiding some secret.

Let's consider the declension of a noun according to the weak type (there are few of them in the language and they need to be memorized), and a verb (irregular - there are also relatively few of them in the language, they also need to be learned) - according to the strong (irregular) type. Verbs of this type can change the root vowels and even in some cases the entire stem during conjugation and, according to special, not always explainable rules, form three main forms of the verb, necessary for the formation of different tenses and moods. Let's take the noun der Seebär (sea wolf) and the verb vergeben (to provide, to give).

Verbs, due to the fact that they denote actions, processes, states, etc., that could have happened in the past, are occurring or taking place now or will take place in the future, also change according to tenses. In German, the system of tense formation of verbs differs significantly from Russian and has simple and complex tenses. To complete the picture, consider the declension of the noun according to the third - feminine type and the conjugation of the verb in the simple past tense Präteritum. Let's take the noun die Zunge (language) and two verbs in the form Präterit: the correct one is testen (to check) and the incorrect one is verzeihen (to forgive).

Learning to conjugate German verbs

You need to master:

- Varieties of verbs. There are five of them in total: regular, irregular, verbs with a separable or inseparable prefix, and verbs ending in –ieren. Each of these groups of verbs has its own conjugation features.

- Groups of strong verbs. In each of these groups or subgroups, strong (irregular) verbs are inflected in the same way. It is more convenient to analyze one such group in one lesson than to study tables in which all strong verbs are given in a row.

- Declension of reflexive verbs or verbs with the reflexive pronoun sich. In general, it does not differ from the general scheme for conjugating weak verbs, but there are nuances.

- Topic "Modal verbs".

- Verbs with two conjugations. They can be declined as both strong and weak; pay special attention to verbs with two meanings (the type of conjugation is determined according to the meaning).

- Declension of German verbs in the past tense (Präteritum, Perfekt, Plusquamperfekt). Many reference books list three popular forms: the infinitive, the simple past tense, and the participle used to form the perfect tense (Partizip II).

- Declension in special forms of the German future tense (Futur I and Futur II).

- Declension of German verbs in different moods (two forms of the subjunctive mood - Konjunktiv I and Konjunktiv II, and the imperative mood, that is, the imperative).

The benefits of learning German

- German is not only one of the most widely spoken languages in Europe, it is also the mother tongue of more than 120 million people. Germany alone has a population of over 80 million, making the country the most populous in all of Europe. German is also the mother tongue of many other countries. This includes Austria, Luxembourg, Switzerland, and Liechtenstein. Knowledge of the German language makes it possible to communicate not only with residents of the above countries, but also with a significant part of Italians and Belgians, French and Danes, as well as Poles, Czechs and Romanians.

- Germany is the third country in the world with the strongest and most stable economy. Germany is one of the world's leading exporters. Germany exports cars, medicines, various equipment and many other goods.

- Knowledge of German creates opportunities for personal development and career growth. In Eastern Europe, companies such as BMW and Daimler, Siemens, or, for example, Bosch require international partners.

- If you are looking for a job in the US, knowing German provides significant advantages because... German companies have numerous representative offices and firms in America.

- One out of ten books in the world is published in German. Germany is famous for its large number of scientists who publish more than 80 thousand books every year. Unfortunately, most of these books are translated only into English and Japanese, where German is in demand. Therefore, knowledge of the German language allows you to read a huge variety of these books and publications in the original.

- German-speaking countries have one of the most significant cultural heritages in the world. Germany has always been associated with the homeland of poets and thinkers. W. Goethe, T. Mann, F. Kafka, G. Hesse are just some of the authors whose works are widely known to all of us. Having good knowledge of the German language, you can read works in the original language and understand the culture of the country of origin.

- By learning German you have the opportunity to travel. In Germany, various exchange programs have been created for schoolchildren and students from different countries of the world, as well as to provide education in Germany.

We have already talked briefly about verb conjugation, and also became acquainted with such a concept as strong, weak, mixed And irregular verbs.

Now we will try to understand in more detail what these concepts mean. The differences between these groups are clearly observed in past tense form (Präterium or else they call it Imperfect) And second participle (Partizip II). That's why Präteritum, Partizip II just like Infinitive, should be considered basic forms of the German verb (die Grund – formen). Therefore, they need to be remembered like this:

Infinitiv – Präteritum – Partizip II.

1) weak: machen – machte – gemacht.

2) strong: lesen – las – gelesen.

3) mixed: kennen – kannte – gekannt.

4) modal: können – konnte – gekonnt.

5) incorrect: sein – war – gewesen.

The largest group in the German language is weak verbs (die schwachen Verben). The conjugation type of some weak verbs forms the forms of newly occurring words: das Licht (light) – ablichten (photocopy), der Saft (juice) – saften (squeeze the juice).

Let us recall that weak verbs so called because when conjugated in all tense forms, they do not change their root vowel. Präteritum is formed using the suffix -e(te), and Parizip II is formed using the prefix -ge and suffix -(e)t(added to the stem of the word):

ask: fragen – frafte – gefragt;

live: leben – lebte – gelebt;

play: spielen – spielt – gespielt.

I would like to draw your attention to the fact that in the German language there is verbs with separable and inseparable prefixes, and also borrowed verbs with suffix –ieren. Verbs with inseparable prefixes and the suffix – ieren in Partizip II do not receive the prefix -ge:

change: verändern – veränderte – verändert;

interest: interessieren – interessierte – interessiert.

Now let's consider strong verbs (die starke Verben). The number of these verbs is limited, and new words are not formed by the type of conjugation of strong verbs. We remember that to strong verbs include verbs which in Präteritum and in Partizip II can change their root vowel or word form. For example, read : lesen – las – gelesen; suggest: bieten – bot – geboten.

Changes in root vowels in strong verbs are subject to a certain rule, so several main types of change can be distinguished.

Type I – root vowels in all tense forms are different:

find: finden – fand – gefunden;

help: helfen – half – geholfen;

start off: beginnen – begann – begonnen;

lie: liegen – lag – gelegen.

Type II – root vowels in Infinitiv and Partizip II are the same:

give: geben – gab – gegeben;

drive: fahren-fuhr – gefahren;

run: laufen – lief – gelaufen.

Type III – root vowels in Präteritum and Parizip II are the same:

write: schreiben-schrieb – geschrieben;

grab: greifen – griff – gegriffen;

fly: fliegen – flog – geflogen.

Mixed verbs (die gemischten Verben)– these are verbs that have the characteristics of strong verbs (alternating root vowel) and weak verbs (suffixes -te, -t). Such verbs 8 in German:

know: kennen – kannte – gekannt;

call: nennen – nannte – genannt;

rush: rennen – rannte – gerannt;

burn: brennen – brannte – gebrannt;

send(transmit on radio/TV): senden – sandte – gesandt;

turn(collapse): wenden – wendete – gewendet;

bring: bringen – brachte – gebracht;

think: denken – dachte – gedacht.

Deserves special attention modal verbs (Modalverben). These are verbs that They do not call the action, but only the attitude towards it. Modal verbs do not have an umlaut in Präteritum and Partizip II. Modal verbs total 6

, you can also add to them  twist verb wissen ( know):

twist verb wissen ( know):

be able, have the physical ability: können – konnte – gekonnt;

be able, have permission tion: dürfen – durfte – gedurft;

must: müssen – mußte – gemußt;

should, b be obliged: sollen – sollte – gesollt;

want, have permission: wollen – wollte – gewollt;

want, desire: mögen – mochte – gemocht;

know: wissen – wußte – gewußt.

Now let's talk about irregular verbs (die unregelmäßigen Verben). You just need to remember this group of verbs, there are only 6 :

be: sein – war – gewesen;

have: haben – hatte – gehabt;

become: werden – wurde – geworden;

go: gehen – ging – gegangen;

stand: stehen – stand – gestanden;

do: tun – tat – getan.

Still have questions? Don't know how to determine the conjugation of a German verb?

To get help from a tutor -.

The first lesson is free!

blog.site, when copying material in full or in part, a link to the original source is required.

Sie. The conjugation paradigm looks like this: ich gehe - du gehst - er (sie, es) geht - wir gehen - ihr geht - sie gehen - Sie gehen.The tense of the German language is intended to establish a temporal relationship between the called action and the moment of speech in absolute use or another action in relative use. In total, there are three time stages: present, past and future tense - they express the beginning of an action in the present, past or future, respectively. Within these stages there are six temporary forms: Präsens, Präteritum (Imperfekt), Perfekt, Plusquamperfekt, Futur I and Futur II. The first two are classified as simple times, the rest - as complex ones. Attribution to one or the other is determined by the complexity of the syntactic structure to which this or that tense corresponds. So, for Präsens only one semantic verb with a personal ending is used, and for Perfekt - an auxiliary and semantic verb in the form of the second participle (Partizip II).

The voice of the German language denotes the direction of action relative to the subject. Active voice (Aktiv) occurs when the action is directed away from the subject, passive (Passiv) - when the subject itself is the object of the influence expressed by the verb. For example: Dann macht Rick die Fenster auf(Active) - Die Fenster werden von Rick aufgemacht(Passiv). Separately, there is a passive voice of the state - stative (Stativ).

There are only three moods in the German language: indicative (Indikativ), subjunctive (Konjunktiv) and imperative (Imperativ).

In addition to finite forms, the German verb has two impersonal forms: the infinitive (Infinitiv) and the participle (Partizip). Each of them, in turn, assumes two more forms. Of these, the most common are Infinitiv I and Partizip II, which, along with Präteritum, form a triad of German verb forms used to construct basic constructions.

German verb tenses

Modern German uses a three-tier tense system consisting of past (Vergangenheit), present (Gegenwart) and future tenses (Zukunft). Within each stage there are six tense forms: one in the present tense, two in the future and three in the past.

Präsens is the simple present tense, which expresses an action occurring at the present moment in time or constantly. It is formed only from the stem of the infinitive with a personal ending. In colloquial speech, this tense can often be a substitute for future tense. For example: Er kommt, glaube ich - I think he will come. In this case, the construction of the present tense is used, contextually understood by the Germans as a construction of the future tense. The non-stylistic use of Präsens in literary language can be observed in constructions like: Ich weiß nicht, ob er kommt - I don’t know if he will come.

After Präsens, the second simple tense is Präteritum- past tense formed from the stem of the infinitive using a suffix -te-(1st and 3rd person singular) for weak verbs or using a special form for strong and irregular verbs. So, for example, for the verb rauchen the form in Präteritum will be rauchte, but for a verb gehen - ging. This tense form is used in a story or message. Example: Ich machte schon die Tür zu - I have already closed the door.

Perfect by its construction - a complex past tense formed from an auxiliary verb haben or sein and the second participle of the semantic verb. The syntactic and grammatical specificity of the sentence where Perfekt is used makes it similar to Plusquamperfekt, but the peculiarities of the use of this tense return it to the simple past tense. Perfect is mainly used in colloquial speech. For example: Die Vögel haben nicht gesungen - The birds did not sing.

Close to Perfect Plusquamperfect also consists of auxiliary verbs and the second participle of the semantic verb, but unlike perfect verbs haben And sein have the form Präteritum - hatte And war in the 3rd person singular. For example: Der Gott hatte alles zerstört - God destroyed everything. In German language theory, this tense is most often represented as "past in the past", so it is more often found in relative use together with Präteritum.

All three past tenses of the German language do not have clear boundaries of use. Thus, the colloquial tense Perfekt can also be used in literature, Präteritum - in colloquial speech, and Plusquamperfekt in written speech does not always take place even with relative use or when mentioning events that happened a long time ago relative to the moment of speech or other action. However, this does not cause confusion. Most often, temporal relationships are traced in context.

Future I And Future II- complex future tenses having a similar structure. In both the first and second tenses an auxiliary verb is used werden and Infinitiv of the semantic verb: for Futur I - Infinitiv I, for Futur II - Infinitiv II. The first future tense, in addition to conveying an action in the future, also has other functions of use: for example, in relative use in literature or even as an order (imperative function). The second future tense is practically not used in modern German. Example: Bis Monatsende wirst du die Lösung finden(Futur I) - Bis Monatsende wirst du die Lösung gefunden haben(Futur II) - By the end of the month you will find a solution.

| Time / Person and number |

Präsens | Präteritum | Perfect | Plusquamperfect | Future I |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1st l. units h. (ich) | arbeite gehe |

arbeitete ging |

habe gearbeitet bin gegangen |

hatte gearbeitet war gegangen |

werde arbeiten werde gehen |

| 2nd person singular h. (du) | arbeitest gehst |

arbeitetest gingst |

hast gearbeitet best gegangen |

hattest gearbeitet warst gegangen |

wirst arbeiten wirst gehen |

| 3rd l. units h. (er, sie, es) | arbeitet geht |

arbeitete ging |

hat gearbeitet ist gegangen |

hatte gearbeitet war gegangen |

wild arbeiten wild gehen |

| 1st l. pl. h. (wir) | arbeiten gehen |

arbeiteten gingen |

haben gearbeitet sind gegangen |

hatten gearbeitet waren gegangen |

werden arbeiten werden gehen |

| 2nd l. pl. h. (ihr) | arbeitet geht |

arbeitetet gingt |

habt gearbeitet seid gegangen |

hattet gearbeitet wart gegangen |

werdet arbeiten werdet gehen |

| 3rd l. pl. h. (sie) and polite f. (Sie) |

arbeiten gehen |

arbeiteten gingen |

haben gearbeitet sind gegangen |

hatten gearbeitet waren gegangen |

werden arbeiten werden gehen |

Nominal verb forms

Infinitive

A German infinitive used independently, that is, outside of infinitive groups, is called independent. In infinitive groups (for example, um zu, an(statt) zu And ohne zu) the infinitive used is called dependent. For example: Die Türe aufzumachen war verboten - Opening the doors was forbidden(independent infinitive with zu); Ich kam rein, ohne anzuklopfen - I entered without knocking(dependent infinitive with zu). Infinitive without a particle zu used with modal verbs, verbs haben(outside structures), nennen, hören, fühlen, sehen, finden, spüren, after verbs helfen, lernen, lehren, bleiben, senden, and also after verbs of motion. In other cases, use the infinitive with a particle zu, including: after adjectives as a nominal predicate, in infinitive groups and constructions like ( haben + zu+ Infinitive and sein + zu+ Infinitiv) .

In relative usage, the first and second infinitives have different functions. So, if the first infinitive expresses simultaneity of actions, then the second - precedence. For example: Martin geht weiter, ohne auf mich zu achten(Infinitive I) - Er ist sehr traurig darüber, seinen Vater verloren zu haben(Infinitiv II).

The syntactic role of the infinitive is not limited solely to being a component of a complex predicate. It acts as:

- Subject: Reiten ist ein großes Vergnügen - Riding a horse is great pleasure; It was a great relief for him that he had found the only possible way out of this difficult situation..

- Definitions: Jeder Bürger dieser Stadt hat das Recht, ausgewählt zu werden - Every citizen of this city has the right to be elected; Der Gedanke, damals nicht sein Möglichstes getan zu haben, quälte den alten Kapitän - The thought that he had not done everything possible then tormented the old captain.

- Add-ons: Jedenfalls hoffen wir darauf, abgeholt zu werden - In any case, we hope that we will be greeted; Er war damals sicher, in seinem Leben nur einmal ein ähnliches Gefühl empfunden zu haben - Then he was convinced that he had experienced such a feeling only once.

- Circumstances: Beeile dich, um zum Unterricht nicht zu spät zu kommen - Hurry up so as not to be late for class.

Communion

The German participle (Partizip) is another nominal form of the verb. There are two German participles: Partizip I and Partizip II. The second participle is the most commonly used, as it is involved in the formation of many German constructions.

The first participle is formed from the stem of the verb using a suffix -(e)nd: learn-end, feier-nd. The second participle uses a stem, a grammatical prefix, to form weak verbs ge- and suffix -(e)t: ge-mach-t, ge-sammel-t, ge-öffn-et. Special forms of Partizip II are found in irregular, strong and preterite present verbs, which receive a prefix ge-, suffix -en and changing the root vowel: sein - gewesen, bringen - gebracht, treiben - getrieben, sterben - gestorben, können - gekonnt, wissen - gewusst .

The first participle always expresses an action that is still in process, that is, unrealized, regardless of what tense the predicate is in. For example: Die aus dem Kino eilenden Mädchen lächelten/lächeln so laut - The girls rushing (hurrying) from the cinema laughed so loudly (laugh). In this case, Partizip I plays the role of definition. It is used as a circumstance in the participial group: Aus dem Kino eilend, lächeln die Mädchen so laut - Rushing out of the cinema, the girls laughed so loudly.

The second participle has a passive meaning, that is, the subject with which it is associated is the object of influence: Das vom Jungen gelesene Buch - The book read by the boy. The use of Partizip II is much wider: it is present as part of the simple verbal predicate in the two complex past tenses of the active voice of the indicative and subjunctive moods, as well as in all tenses of the passive voice. For example: Heute sind sie früher ausgegangen - Today they left early; Der Text war zweimal vorgelesen worden - The text was read twice. The second participle can play the role of an adverbial adverb, an object, and less often a subject, and also form participial groups. For example: Die von mir gekaufte Hose steht mir nicht - The trousers I bought do not suit me .

Pledge

There are two voices in German: active (Aktiv) and passive (Passiv). The action on the part of the subject in a sentence with active voice is aimed at a third-party object, that is, an object. In the passive voice, the subject itself is the object of influence. Accordingly, the sentence itself, where one or another voice is used, is also called active and passive. For the formation of the active voice of all tenses, see above in the section German verb tenses.

The passive voice is formed using an auxiliary verb werden and Partizip II of the semantic verb. In the complex past tenses Perfekt and Plusquamperfekt the verb is taken as auxiliary sein, necessary to form a complex tense, and a verb werden in a special form worden, which forms the passive. Thus, the chain of passive voice of all tenses will look like: Der Artikel wird von mir vorgelesen(Präsens) - Der Artikel wurde von mir vorgelesen(Präteritum) - Der Artikel ist von mir vorgelesen worden(Perfect) - Der Artikel war von mir vorgelesen worden(Plusquamperfekt) - Der Artikel wird von mir vorgelesen werden(Futur).

| Time / Person and number |

Präsens | Präteritum | Perfect | Plusquamperfect | Future I |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1st l. units h. (ich) | werde gesucht | wurde gesucht | bin gesucht worden | war gesucht worden | werde gesucht werden |

| 2nd person singular h. (du) | wirst gesucht | wurdest gesucht | best gesucht worden | warst gesucht worden | wirst gesucht werden |

| 3rd l. units h. (er, sie, es) | wild gesucht | wurde gesucht | ist gesucht worden | war gesucht worden | wild gesucht werden |

| 1st l. pl. h. (wir) | werden gesucht | wurden gesucht | sind gesucht worden | waren gesucht worden | werden gesucht werden |

| 2nd l. pl. h. (ihr) | werdet gesucht | wurdet gesucht | seid gesucht worden | wart gesucht worden | werdet gesucht werden |

| 3rd l. pl. h. (sie) and polite f. (Sie) |

werden gesucht | wurden gesucht | sind gesucht worden | waren gesucht worden | werden gesucht werden |

Stativ, or state passive (Zustandpassiv), conveys the result of an action. The cabinet chain for all times looks like: Der Artikel ist vorgelesen(Präsens) - Der Artikel war vorgelesen(Präteritum) - Der Artikel ist vorgelesen gewesen(Perfect) - Der Artikel war vorgelesen gewesen(Plusquamperfekt) - Der Artikel wird vorgelesen sein(Futur) .

There are three types of passive voice: one-member, two-member and three-member. The first occurs when neither the object nor the subject is specified. The second is when there is only an object. The third is both object and subject.

Mood

The German language system of moods includes three moods: indicative (Indikativ), subjunctive (Konjunktiv) and imperative (Imperativ). For indicative tenses, see German Verb Tenses.

Präsens Konjunktiv formed from the infinitive stem, suffix -e- and personal endings (except for the 1st and 3rd person singular) and most often expresses a feasible desire, sometimes an order or concession. Narpimer: Es lebe der Frieden in der ganzen Welt - Long live world peace.

Weak verbs in Präteritum Konjunktiv repeat the preterite of the indicative mood. Strong verbs are formed from a preterite stem with a suffix -e and with umlaut of the root vowel. Preterital forms of the subjunctive mood express impossible (unreal) actions in the present that are thought but do not occur. For example: Ich ginge gern ins Museum, aber ich bin gerade beschäftigt - I would love to go to the museum, but I'm busy right now.

Perfect Konjunktiv And Plusquamperfekt Konjunktiv use auxiliary verbs haben And sein in the forms Präsens Konjunktiv and Präteritum Konjunktiv, respectively, and Partizip II of the semantic verb. The perfect in subordinate clauses conveys the precedence of its action in relation to the action in the main clause, regardless of the time of the main clause. For example: Ich tue/tat, als ob ich das Mädchen schon gesehen habe - He tells/told me that he went for a walk with her. The plusqua perfect, like the preterite, conveys an unreal desire, but in the past tense. For example: Wäre ich nur nicht so spät gekommen - If only I had not come so late.

Futur I Konjunktiv And Futur II Konjunktiv form the subjunctive mood through the Präsens Konjunktiv of the verb werden and Infinitiv I and Infinitiv II of the semantic verb. The future tense in a subordinate clause (by analogy with the perfect) reflects the sequence of events in which the action in the main clause occurs earlier. For example: Jeder Mensch träumt, dass er glückliches Leben haben werde - Every person dreams that his life will be happy.

| Time / Person and number |

Präsens | Präteritum | Perfect | Plusquamperfect | Future I |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1st l. units h. (ich) | lese | lernte käme |

habe gesagt sei gegangen |

hätte gesagt where are you going? |

Werde sagen werde gehen |

| 2nd person singular h. (du) | lesest | lerntest kämest |

habest gesagt seist gegangen |

hättest gesagt wärest gegangen |

werdest sagen werdest gehen |

| 3rd l. units h. (er, sie, es) | lese | lernte käme |

habe gesagt sei gegangen |

hätte gesagt where are you going? |

Werde sagen werde gehen |

| 1st l. pl. h. (wir) | lesen | lernten kämen |

haben gesagt seien gegangen |

hätten gesagt wären gegangen |

werden sagen werden gehen |

| 2nd l. pl. h. (ihr) | leset | lerntet kämet |

alphabet seiet gegangen |

hättet gesagt wäret gegangen |

werden sagen werden gehen |

| 3rd l. pl. h. (sie) and polite f. (Sie) |

lesen | lernten kämen |

haben gesagt seien gegangen |

hätten gesagt wären gegangen |

werden sagen werden gehen |

Construction with Präteritum Konjunktiv verb werden with the first and second infinitive it forms Konditionalis I and Konditionalis II: the first conditionalis replaces the Präteritum Konjunktiv in cases where its forms coincide with the indicative, the second conditionalis expresses an unreal action (like the plusquaperfect). The passive conjunctive voice for all tenses is implemented according to the scheme of the passive indicative mood using the conjunctive auxiliary verb.

In addition to the standard ways of forming an imperative, there are also other ways of expressing the impulse to action. These include the infinitive ( Warten! Abführen!), second communion ( Rauchen verboten!), use of second person ( Du machst das! Ihr fliegt raus!), nominal parts of speech ( Ruhe! Achtung!) and passive without subject ( Jetzt wird geschlafen!) .

Verb word formation

Verb semiprefixes include: ab-, an-, auf-, aus-, bei-, durch-, ein-, entgegen-, entlang-, gegenüber-, hinter-, mit-, nach-, ob-, über-, um-, unter- , vor-, wider-, zu-. All these morphemes have the property of being separated from the root and occupying a final position in the sentence in certain grammatical cases (for example, in the present or imperative of the second person singular), as well as skipping the grammatical prefix ge- in the form of the second participle of verbs. The second property of these morphemes is stress. Prefixes: be-, de-, dis-, durch-, emp-, ent-, er-, ex-, ge-, hinter-, in-, kon-, miss-, per-, prä-, re-, sub- , trans-, über-, um-, unter-, ver-, wider-, zer-, - unlike semi-prefixes, they are not able to be separated from the root and do not miss the grammatical prefix. Verb suffixes -ch(en), -el(n), -l(n), -er(n), -ster(n), -ier(en), -ig(en), -sch(en), -s (en), -z(en) either semantically neutral or expressing narrow meanings.

There are two types of frequency components of verbs:

- The first frequency component occupies the initial position and corresponds to the adverbs: auseinander-, da-, daher-, dahin-, daneben-, dar-, darein-, davon-, dazu-, dazwischen-, drauflos-, einher-, empor-, entzwei-, fehl-, fern-, fertig- , fest-, fort-, frei-, gleich-, her-, herab-, heran-, herauf-, heraus-, herbei-, herein-, hernieder-, herüber-, herum-, herunter-, hervor-, herzu -, hierher-, hin-, hinab-, hinan-, hinauf-, hinaus-, hindurch-, hinein-, hintereinander-, hinterher-, hinüber-, hinunter-, hinweg-, hinzu-, hoch-, los-, nieder-, tot-, umher-, voll-, voran-, voraus-, vorbei-, vorher-, vorwärts-, weg-, weiter-, wieder-, zurecht-, zurück-, zusammen-.

- The second frequency component occupies the final position and is a verb: -arbeiten, -beißen, -biegen, -bleiben, -blicken, -brechen, -bringen, -drücken, -fahren, -fallen, -finden, -fliegen, -führen, -geben, -gehen, -haben, -halten , -hauen, -heben, -holen, -kommen, -können, -kriegen, -lassen, -laufen, -leben, -legen, -liegen, -machen, -müssen, -nehmen, -reden, -reichen, - reißen, -richten, -rücken, -rufen, -sagen, -schaffen, -schauen, -scheißen, -schlagen, -schreiben, -sehen, -sein, -setzen, -sitzen, -spielen, -sprechen, -springen, -stecken, -stehen, -steigen, -stellen, -stoßen, -stürzen, -tragen, -treiben, -treten, -tun, -werden, -werfen, -wollen, -ziehen.

Historical grammar of the German verb

The early development of complex temporal relations in the formation of auxiliary verbs was determined by the reverse process - the reduction of (unstressed) verb endings into an indifferent -e, as a result of which it became possible to form the future and relative tenses, as well as the passive voice. The number of persons does not change, but is determined by the presence of a personal pronoun. The system of moods develops towards stylistic differentiation of modal relations.

Development of temporary forms

Development of non-personal forms

The infinitive and participle are derived from a verbal noun and an adjective. The development of the infinitive is associated with the use of nominal word-forming suffixes and, in general, does not go away from the general process of formation of the indefinite form of the Indo-European languages. The fundamental difference between the infinitive in New High German and the contemporary infinitive, for example, in Slavic languages, is that the German infinitive has not lost its connection with the noun (many verbs can be substantivized, such as schreiben - das Schreiben; some of them have become full-fledged nouns, such as nouns das Vertrauen, das Wesen) .

The first participle in Old High German is formed using a Germanic suffix -nd and has a weak and strong declination. In most cases, the first participle is used as a form of the present tense in modern German, but historically its temporal meaning is associated with the time of action in a particular sentence (this does not exclude its relationship to the past tense in a modern German sentence). For example, in the line from the Nibelungenlied " daȥ wil ich iemer dienende umbe Kriemhilde sîn" and in the modern sentence " gestern sah ich die aufgehende Sonne» The first participle combines freely with the past tense of the verb and also takes on the meaning of the past tense.

The second participle, as noted above, had two types of formation - strong and weak. The strong was formed using the suffix -an, weak - with dental -d. In the Middle and Early High German periods the prefix appears ge-. Just as the first participle is associated with the present tense, the second participle is associated with the past tense. However, its temporary meaning is associated with specific usage (the type is determined contextually), as, for example, in the phrases das gekaufte Haus, der besetzte Platz, der gefallene Stein(perfect form) and das geliebte Kind, die gepriesene Schönheit(imperfect view) .

See also

Notes

- Verb // Linguistics. / Ch. ed. V. N. Yartseva. - 2nd ed. - M.:, 1998. - 658 p. - ISBN 5-85270-307-9

- Kozmowa R. Zur Grammatikalisierung der Kategorien des Verbs: Tempus, Genus und Modus. - 2004. - P. 235-242.

- Krongauz M. A. Verb prefix, or time coordinate / Answer. ed. N. D. Arutyunova, T. E. Yanko. - M.: Indrik, 1997. - P. 152-153.

- , pp. 3-6

- Verben (German). Lingolia.com. Archived

- Smirnova T. N. German. Intensive course. Initial stage. - M.: Onyx, 2005. - P. 57-59. - ISBN 5-329-01422-0

- Balakina A. A. German modal verbs: From etymology to pragmatics. Archived

- German Grammar (Reference Book) / Verb (Verb) / Modal Verbs. StudyGerman.ru. Archived from the original on August 12, 2012. Retrieved July 12, 2012.

- , pp. 23

- German Grammar (reference book) / Verb (Verb) / Transitive and intransitive verbs. StudyGerman.ru. Archived from the original on August 12, 2012. Retrieved July 12, 2012.

- German Grammar (Reference Book) / Verb (Verb) / Reflexive Verbs. StudyGerman.ru. Archived from the original on August 12, 2012. Retrieved July 12, 2012.

- , pp. 7-9

- Dubová J. Einführung in die Morfologie der deutschen Sprache. - Olomouc: UPO, 2006. - pp. 11-12. - ISBN 80-244-1196-2

- Duden. Grammatik der deutschen Gegenwartssprache, 4. Auflage. - Mannheim, Leipzig, Wien, Zürich, 1984. - pp. 123-143.

- Noskov S. A.§ 62. Basic methods of word formation in the German language // German language for those entering universities. - Mn. : High. school, 2002. - P. 339. - ISBN 985-06-0819-6

- , pp. 6-9

- German language // Linguistics. Big encyclopedic dictionary / Ch. ed. V. N. Yartseva. - 2nd ed. - M.: Great Russian Encyclopedia, 1998. - 658 p. - ISBN 5-85270-307-9

- German language. Around the world. Archived from the original on August 12, 2012. Retrieved July 12, 2012.

- Zeitformen (German). Lingolia.com. Archived from the original on August 12, 2012. Retrieved July 12, 2012.

- Zeitformen / Tempus (German). Mein Deutschbuch. Archived from the original on August 12, 2012. Retrieved July 15, 2012.

- Claudia Maienborn. Das Zustandpassiv: Grammatische Einordnung, Bildungsbeschränkungen, Interpretationsspielraum (German). Archived from the original on August 12, 2012. Retrieved July 15, 2012.

- , pp. 9-19

- German grammar. - M.: Lawyer, 2001. - P. 34-42.

- Verb in the present tense (Präsens). De-Online. Archived from the original on August 12, 2012. Retrieved July 12, 2012.

- Kremer P., Nimtz D. Deutsche Grammatik, 7. Aufl. - Neuss und Münster, 1989. - P. 68. - ISBN 3-486-03163-5

- Präteritum oder Perfect? (German). Belles Lettres – Deutsch für Dichter und Denker. Archived from the original on August 12, 2012. Retrieved July 12, 2012.

- Kurze deutsche Grammatik. - Vilnius, 2001. - pp. 22-24. - ISBN 9989-869-69-2

- Kessel, Reimann. Basiswissen Deutsche Gegenwartssprache. - Tübingen, 2005. - P. 81. - ISBN 3-8252-2704-9

- Marfinskaya M. I., Monakhova N. I. German grammar. - M.: Lawyer, 2001. - P. 40.

- Der Gebrauch des Präteritums und des Perfekts (German). Deutsche Grammatik 2.0. Archived from the original on August 12, 2012. Retrieved July 15, 2012.

- Duden. Die Grammatik, 7. Aufl. - 2005. - P. 729–731. - ISBN 3-411-04047-5

- Zeitformen in der deutschen Grammatik: Der Gebrauch der Tempora im Überblick (German). Worterblog. Archived from the original on August 12, 2012. Retrieved July 15, 2012.

- Norbert Richard Wolf. Struktur der deutschen Gegenwartssprache II (S. 25) (German). Archived from the original on August 12, 2012. Retrieved July 12, 2012.

- Niedersächsische Hilfsverben (German). Bausteine des Niedersächsischen (Niederdeutschen, Plattdeutschen). Archived from the original on August 12, 2012. Retrieved July 13, 2012.

- , pp. 25-38

- Indefinite form of the past (perfect) tense (Infinitiv Perfect). De-Online. Archived from the original on August 12, 2012. Retrieved July 12, 2012.

- Infinitivsätze (German). Mein Deutschbuch. Archived from the original on August 12, 2012. Retrieved July 15, 2012.

- Infinitiv mit und ohne "zu" (Czech). FEL ČVUT . Archived from the original on August 12, 2012. Retrieved July 15, 2012.

- , pp. 35-38

- Present and past participles (Partizip 1, Partizip 2). De-Online. Archived from the original on August 12, 2012. Retrieved July 12, 2012.

- , pp. 54-58

- Noskov S. A.§ 41. Formation of the past participle // German language for those entering universities. - Mn. : High. school, 2002. - pp. 318-319. - ISBN 985-06-0819-6

- Vaitekūnienė V., Girdenienė S. Kurze deutsche Grammatik. - Vilnius, 2001. - pp. 35-36. - ISBN 9989-869-69-2

- , pp. 55

- Smirnova T. N. German. Intensive course. Initial stage. - M.: Onyx, 2005. - P. 101. - ISBN 5-329-01422-0

- , pp. 42-43

- , pp. 42-43

- , pp. 41-42

- , pp. 43-54

- Arsenyeva M. G., Zyuganova I. A. German grammar. - St. Petersburg. : Union, 2002. - P. 178.

- Glück H. Metzler Lexikon Sprache. - Stuttgart, Weimar: Verlag J. B. Metzler, 2005. - P. 338.

- Vaitekūnienė V., Girdenienė S. Kurze deutsche Grammatik. - Vilnius, 2001. - pp. 30-31. - ISBN 9989-869-69-2

- Konjunktiv (German). Lingvo4u.de. Archived from the original on August 12, 2012. Retrieved July 15, 2012.

- , pp. 47

- Noskov S. A.§ 34. Formation and use of imperative forms // German language for those entering universities. - Mn. : High. school, 2002. - pp. 311-313. - ISBN 985-06-0819-6

- Imperativ (German). Lingvo4u.de. Archived from the original on August 12, 2012. Retrieved July 15, 2012.

- Dictionary of word-formation elements of the German language / Under the guidance of. M. D. Stepanova. - M.: Rus. lang., 1979. - P. 14, 530-532.

- German Grammar (Reference Book) / Verb (Verb) / Verbs with separable prefixes. StudyGerman.ru. Archived from the original on August 12, 2012. Retrieved July 12, 2012.

- German Grammar (reference book) / Verb (Verb) / Verbs with inseparable prefixes. StudyGerman.ru. Archived from the original on August 12, 2012. Retrieved July 12, 2012.

- Zuev A. N., Molchanova I. D., Muryasov R. Z. et al. Dictionary of word-formation elements of the German language / Under the guidance of. M. D. Stepanova. - M.: Rus. lang., 1979. - pp. 513-518.

- Zhirmunsky V. M. History of the German language. - M.: Publishing house of literary materials in foreign languages. lang., 1948. - pp. 213-215.

- Zhirmunsky V. M. History of the German language. - M.: Publishing house of literary materials in foreign languages. lang., 1948. - P. 215.

- Moskalskaja O.I. Deutsche Sprachgeschichte. - M.: Academy, 2003. - P. 89-90. - ISBN 5-7695-0952

- Fabian Bros. Mittelhochdeutsche Kurzgrammatik. - pp. 20-23.

- Zhirmunsky V. M. History of the German language. - M.: Publishing house of literary materials in foreign languages. lang., 1948. - P. 232-235.

- Zhirmunsky V. M. History of the German language. - M.: Publishing house of literary materials in foreign languages. lang., 1948. - P. 239-245.

- Substantivierte Verben (German). GfdS. Archived from the original on August 12, 2012. Retrieved July 15, 2012.

- Zhirmunsky V. M. History of the German language. - M.: Publishing house of literary materials in foreign languages. lang., 1948. - pp. 241-243.

Literature

- Mackensen L. German. Universal reference book. - M.: Aquarium, 1998. - 592 p. - ISBN 5-85684-101-8

- Myshkovaya I. B. German verb tenses. - St. Petersburg. : Victory, 2007. - 96 p. - ISBN 978-5-91281-007-7

- Pogadaev V. A. German. Quick reference. - M.: Eksmo, 2003. - 318 p. - ISBN 5-8123-0155-7

- Helbig G., Buscha J. Deutsche Grammatik. - Berlin: Langenscheidt, 2007. - 736 p. - ISBN 978-3-468-49493-2

- Hoberg R. Der kleine Duden. Deutsche Grammatik. - Wien, Zürich, 1988. - ISBN 3-411-02182-9

- Pahlow H. Deutsche Grammatik - einfach, kompakt und übersichtlich. - Leipzig: Engelsdorfer Verlag, 2010. - 135 p. -

Verbs in German one of the most important top topics. It is very extensive and requires closer attention. In this article we will touch on verb categories.

Main characteristics and categories of the verb

Verb categories

So, verbs are 70% of the entire language. They represent actions. Knowing the mechanisms of verb functioning and being able to apply them is already “speaking” a foreign language.

What are German verbs?

Pure verb in indefinite form = warp+ neutral ending –en(rarely just -n):

mach en = do(specifically)

tu n = do(abstract)

lach en = laugh

denk en = think

In addition to the ending, a prefix (one or more) can be added to the stem of the verb. It can be detachable or non-detachable. Detachable attachments are shock. Inseparable - unstressed. In a sentence, the logical stress falls on the separable prefix. For example:

Here you can see how the prefix, separating, goes to the end of a sentence or phrase. Moreover, as in English, prefixes can radically affect the new meaning of a word:

In a sentence, the verb is most often a predicate and, in agreement with the subject, has the following grammatical categories: person, number, tense, mood and voice.

|

Präsens |

Ich schreibe einen Brief. |

I'm writing a letter. |

|

Präteritum |

Ich schrieb einen Brief. |

I was writing a letter. |

|

Ich habe einen Brief geschrieben. |

I was writing a letter. |

|

|

Plusquamperfect |

Nachdem ich einen Brief geschrieben hatte, schlief ich ein. |

After I wrote the letter, I fell asleep. |

|

Ich werde einen Brief schreiben. |

I will write a letter. |

|

|

Morgen um 15 Uhr werde ich diesen Brief geschrieben haben. |

Tomorrow at three o'clock I will (already) write this letter. |

Mood is the relationship between action and reality. How real or unreal it is. This also includes the expression of requests, orders and calls for action.

For one mood or another, the following formulas and tenses are used:

|

Indicative mood - real action in all three time planes: |

Präsens, Präteritum, Perfekt, Plusquamperfekt, Futur I, Futur II |

|

Subjunctive mood - desired, unrealistic, conditional action: Indirect speech: |

Konjuntiv 2 Ich würde heute ins Kino gehen.

Konjunktiv 1 |

|

Imperative - order, request, call |

du-Form: Sag( e)! Tell! wir-Form: Sag en wir! Let's say! Summon: + lassen(give (opportunity) wir (2 Person):Lass uns Kaffee trinken! Let's have some coffee! |

active action(action is performed by the subject)

passive action(action directed at the subject)

Unlike the Russian language at the German verb no species category, i.e., it is clearly impossible to determine without context whether an action is ongoing or has already ended only by the form of the verb. For example:

Remember! Most native German speakers don't know half of what you learned from this article. Foreigners who find themselves in a language environment begin to learn it like children, observing, imitating, making mistakes, but ultimately moving forward and improving with each attempt. This path can be made easier and shorter by applying the acquired grammatical knowledge.

The meaning of modal verbs. Modal are called such verbs that express not the action itself, but only attitude to action(Wed.: We we want study well. We Can study well. We should study well). Therefore, modal verbs in German are usually not used independently, i.e. without a second verb, which expresses the desired, possible or necessary action itself. This second verb always answers the question “what to do?” and stands in the infinitive, as in Russian ( Wed.: We want - what to do? - study well). Basic modal verbs in German: können(to be able), mussen(should) wollen(want). They are very common, without them it is often impossible to express a thought.

In Russian, opportunity, necessity, and desire can be expressed in two ways:

Possibility 1. We Can. = 2. Us Can.

Obligation 1. We should. = 2. Us need (must).

Desire 1. We we want. = 2. Us I want to.

In German, only the first method is used.

Wed:

They can(can) ( they can) work in the laboratory. Sie können im Labor arbeiten.

Except können, müssen, wollen modal verbs are also often used sollen And durfen.

Verb sollen close in value to mussen.

Wed.:

You want (you want) to visit the museum. Sie wollen das Museum be suchen.

Wir müssen (Wir sollen) jetzt viel arbeiten. We must (forced, we have to), we must (obliged, we should) work hard now.

Verb durfen close in value to können:

Wir können (Wir dürfen) dieses Buch in der Bibliothek bekommen. We can (=have the opportunity)

We can (=have the right, permission) to get this book from the library.

In most cases the differences in meaning between mussen And sollen(to be forced and to be obliged), between können And durfen(to have the opportunity and to have permission) are not very significant, they can be ignored and only the verbs können (to be able) and müssen (to have to) can be used in speech.

Task 1. Indicate which modal verbs should be used to say in German:

1. We need to finish work tomorrow. 2. Who should make a presentation at the seminar? 3. I want to take the exam in December. 4. Misha wants to play sports. 5. You can borrow foreign journals from the department or the library. 6. We can work in the reading room until seven o’clock in the evening.

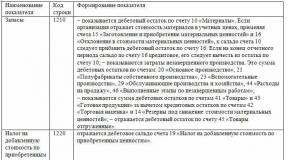

Conjugation of modal verbs in the present

In present, all modal verbs have special singular forms (plural forms are formed according to the general rule):

| wollen | können | mussen | durfen | sollen | |

| ich | will | kann | muss | darf | soll |

| du | willst | kannst | must | darfst | sollst |

| er | will | kann | muss | darf | soll |

As can be seen from the table, the peculiarity of their conjugation is that they do not have personal endings in the 1st and 3rd person singular. numbers (these forms are the same), and also all (except sollen) change the root vowel into singular. number (these forms need to be remembered).

Task 2. Indicate which forms of the modal verbs given in brackets should be used instead of gaps in the following sentences:

1…. er den Text ohne Wörterbuch übersetzen? (können) 2. Ich... heute meinen kranken Freund besuchen. (wollen) 3. Welches Thema... du zum Seminar vorbereiten? (sollen) 4. Mein Freund... seinen Eltern helfen. (mussen)

Word order in a sentence with a modal verb

As can be seen from the above examples, in a German sentence the modal verb takes the place of the predicate (i.e. 2nd or 1st), and the verb in the infinitive, expressing the action itself, is not used (unlike the Russian language) immediately after the modal , but at the very end of the sentence.

The negation nicht with modal verbs (unlike all others) can be used immediately after the modal verb (but can also be used before the infinitive).

Task 3. Indicate in what order the German words should be used to say:

1. Tomorrow I want to visit my school friend. besuchen; morgen; will; meinen Schulfreund; ich.

2. When do you need to write a test? die Kontrollarbeit; wann; musst; schreiben; du?

3. Can you help me with German? du; in Germany; kannst; helfen; mir?

4. She can have good grades in all subjects. gute Noten; kann; haben; sie; in Allen Fachern.

5. Today we cannot work in the reading room. wir; im Lesesaal; arbeiten; heute; nicht; können.

6. He should be at home in the evening. er; muss; zu Hause; sein; am Abend.

7. I can't read English. ich; kann, nicht; Englisch; lesen.

Man with modal verbs müssen and können

When they want to say that some action must or can be performed without indicating who exactly, they use a combination of man with modal verbs:

necessary, necessary - man muss (man soll)

you can - man kann (man darf)

You need to read a lot. (not specified to whom) Man muss viel lesen.

He needs to read a lot. (person indicated) Er muss viel lesen.

Can I finish my work today? (not specified to whom) Kann man die Arbeit heute beenden?

Can I finish my work today? (person indicated) Kann ich die Arbeit heute beenden?

As can be seen from these examples, man and the modal verb change places so that the modal verb always ends up in the place of the predicate, that is, in 2nd or 1st place.

If they want to say that this or that action is not necessary or cannot be performed, then they add the negation nicht:

not necessary, not necessary - man muss (soll) nicht impossible - man kann (darf) nicht

For example:

You don't need to finish work today. Man muss nicht die Arbeit heute beenden.

You can't work in peace here. Hier kann man nicht ruhig arbeiten.

Task 4. Indicate which of the following sentences should be translated using the combination man muss or man kann:

1. He needs to prepare a report. 2. I can go home for three days. 3. Special literature should be read without a dictionary. 4. Can I take books home from the reading room? 5. Can I come to you in the evening?

Video on the topic “Modal verbs in German”: